What is Yiddish? Yiddish was the language spoken by the majority of Eastern and Central European Jews over the last millenium. It is a Germanic language with some Slavic and Hebrew elements in both its vocabulary and its grammar. So, it sounds like German with a twist of Hebrew. But it uses the Hewbrew alphabet. So in writing, it looks like Hebrew, with no hint of German.

It had over 10 million speakers at the eve of World War 2, with large communities of speakers in what is now Russia, Ukrayne, Poland, Romania, but also in the USA, England, Mexico, Argentina, and even Australia.

The Holocaust drastically reduced the number of Yiddish speakers, compounded by the widespread migration of Eastern European Jews worldwide, and ensuing assimilation into the host society in subsequent generations. Yiddish was further weakened by the emergence of Hebrew as the chief language of Israel, and by state oppression in the Soviet Union.

Yiddish has been widely perceived to be in terminal decline with an ever-decreasing number of speakers. As a result, Yiddish is now classified as ‘definitely endangered’ by UNESCO, considered ‘at risk’ by the Endangered Languages Project, and recognised as a minority language by the European Union’s Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.

Who speaks Yiddish today? Yiddish continues to be a native and daily language for strictly orthodox (Haredi) communities. Haredi communities live in Bnei Brak near Tel Aviv and Jerusalem's Mea Sharim nighbourhoods in Israel, in the New York area in the US, in Antwerp, Belgium and here in the UK, too.

Most Yiddish-speaking Haredi Jews are members of the Hasidic movement, a spiritual movement comprising of over a dozen subgroups following different rabbinic dynasties tracing themselves back to various geographic locations in Eastern Europe. The subgroups are usually named after these locations, e.g. Satmar, Bobov, Ger, etc.

The UK's largest Haredi community (ca. 40,000) lives in Stamford Hill, London. Survey data claim that over 75% of adults and children of this community are 'fluent' in Yiddish, and over 50% use it as 'the main language at home’. 1

What do we know about contemporary Hasidic Yiddish? There is currently very little scholarly work on the language practices of present-day Yiddish speakers in Hasidic communities. This may simply be due to the fact that many scholars are unaware of the pervasive extent of Yiddish use in the Hasidic communities, or perhaps due to the degree of cultural divide between the Haredi and secular Yiddishist communities.

This project is the first ever systematic study of the language of the Stamford Hill Haredi community.

Our research group I work with Lily Kahn, an expert on Jewish languages and minority languages, from the Department of Hebrew and Jewish Studies (UCL), Zoë Belk, a Postdoctoral Researcher in theoretical linguistics and Sonya Yampolskaya, a Postdoctoral Researcher in sociolinguistics.

Shifra Hiley, Izzy Posen and Eli Benedict have been our invaluable Research Assistants.

We have a long-standing collaboration with Mendy Cahan, the Founding Director of the YUNG YiDiSH Library and Cultural Centre. He is our expert consultant on Hasidic Yiddish.

Our research We have been conducting dozens of interviews with native speakers of from Stamford Hill and have been surveying a large amount of published written material. Our aim has been to provide a linguistic description of some of the major aspects of Yiddish, as spoken by the Stamford Hill Hasidic community and to address the question whether and to what extent the Yiddish of Stamford Hill is different from pre-war Yiddish.

Gut? Git! Yiddish had many dialects even before World War 2. One of the characteristic differences between the dialects is how they pronounce the word 'good'. In Standard Yiddish and in the Northeastern dialect, it is pronounced with the sound u as in gut, while in Central Yiddish it is pronounced with the sound i as in git.

Stamford Hill Hasidic Yiddish speakers follow the Central dialectal pronunciation, as you can hear from our Stamford Hill speaker, Izzy Posen, in this video. (Dr Lily Kahn, the interviewer's pronunciation follows the Standard Yiddish pronunciation.)

This is not surprising as most of the ancestors of current day Hasidic Yiddish spoke the Polish and Hungarian dialects, which are part of Central Yiddish dialect region.

Rapid and pervasive language change An important finding of our work is that contemporary Hasidic Yiddish in Stamford Hill differs from Standard Yiddish, and even from the pre-War Central Yiddish dialect, in its grammar. Rapid and pervasive language change took place since World War 2.

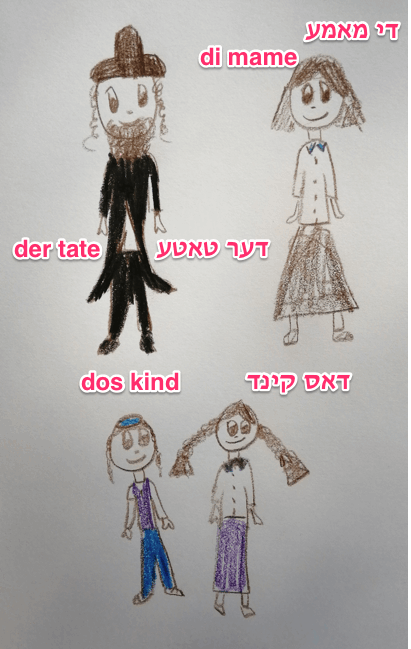

der - di - dos In pre-War Yiddish, and in Standard Yiddish to this day, every noun in Yiddish has what we call gender. As in most other Germanic languages, the article 'the' has a different form depending on the gender of the noun. The names of male entities, such as 'the father', 'the man', etc take the form der. Nouns depicting females, such as 'the mother', 'the woman' come with the form di. There are also nouns that count as neuter gender in the grammar, such as 'the child'; these appear with the article in the form dos.

If an adjective is used next to the noun, its form needs to change to depending on the gender of the noun. So in Yiddish, we say der hoykher tate 'the tall father', but di hoykhe mame 'the tall mother'.

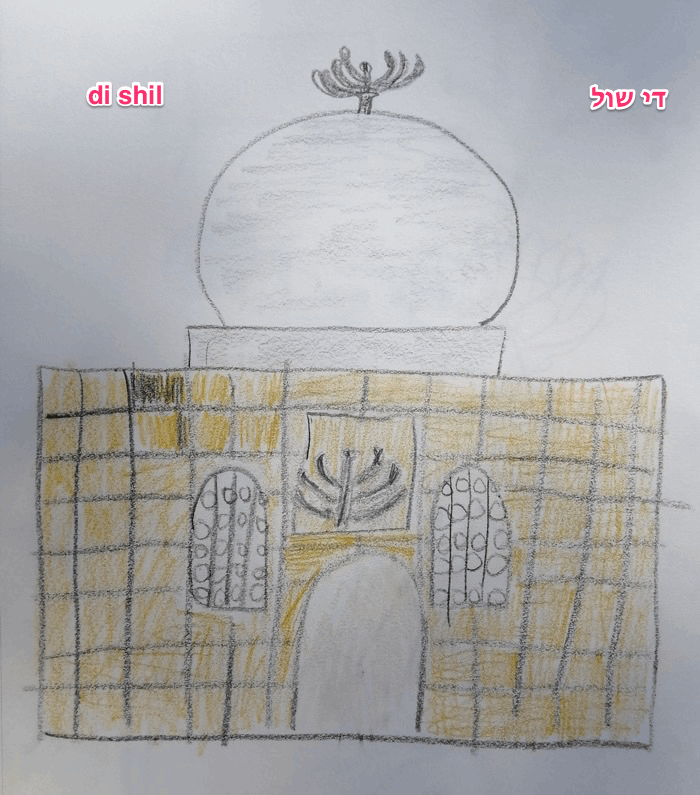

Even nouns whose meaning is neither male nor female are classified as masculine, feminine or neuter for the purposes of the grammar. So, words like 'table' and 'tree' are masculine and thus use the form der, while words like 'synagogue' or 'flower' are feminine, so use the form di. Neuter nouns, with dos, include nouns like 'book' or 'heart'. As the choice of gender is more or less random, a learner has to learn for each noun which gender they are, in order to be able to use the noun with article 'the'.

And also dem... To complicate matters further, the form of the article changes depending on whether the noun is the subject or the object of the sentence or if it attaches to a preposition (e.g. like 'in', 'on', 'by', 'for', etc.). This may all sound very complicated, but it is perhaps easier to understand how this works if one thinks of English pronouns. The form 'they' is used as a subject of the sentence, as in 'They are nice.' but as an object or next to a preposition, one has to use the form 'them', as in 'I like them'. In Yiddish, a masculine noun would take 'der' when it is the subject, but a different form 'dem' when it is the object of the sentence or next to a preposition. Feminine nouns take 'di' both in subject and object position, but they take 'der' when the noun appers next to a preposition. This is called grammatical case. It is only used for pronouns in English, but all nouns used to mark grammatical case in pre-War Yiddish.

No gender, no case Contemporary speakers in Stamford Hill do not use gender or case distinctions on nouns anymore. For them the definite article only takes one form, 'de', pronounced with the same vowel as English 'the', called schwa. This does not seem to be a direct influence of English, however, as the same form is used by Hasidic Yiddish speakers from other areas, such as Bnei Brak and Jerusalem in Israel, like this speaker from Bnei Brak in Israel.

This is a major change in the grammar. English for instance underwent the same change, i.e. loss of case and gender, over several centuries. This kind of change is also pervasive: it changes the linguistic character of the language. Loss of case in particular has repurcussions for other parts of the grammar, in particular, for word order rules.

We believe that the most important reason why this rapid and pervasive change took place is due to the cataclysmic effect of the Holocaust on the speakers and on the language itself. Communities were destroyed, speakers dispersed to a geographically vast area around the globe and language transmission was disrupted after the War.

Our research has underlined the critical need for further linguistic research into this topic. We are currently studying the grammar of Contemporary Hasidic Yiddish as spoken by Hasidic Jews worldwide in a 3-year research project funded by the AHRC.

References

1 Holman, C. & N. Holman. 2002. Torah, Worship and Acts of Loving Kindness: Baseline Indicators for the Charedi Community in Stamford Hill. Interlink Foundation.